I had intended to catch up with a friend in Missoula, Montana, but got stuck in Idaho. I knew only three facts about the state.

I had intended to catch up with a friend in Missoula, Montana, but got stuck in Idaho. I knew only three facts about the state.1. Idahoans were big on spuds. (The number plates boasted of 'famous potatoes'. Those in neighbouring states clearly did not attract the same level of public interest.)

2. The volcano movie Dante's Peak was filmed at Coeur d'Alene in the far north-west. As a disaster movie it was ... well ... disastrous.

3. Vicki Lester claimed that she was born in a trunk at the Princess Theatre in Pocatello, Idaho. Of course, she was only lowly Esther Blodgett then.

But Idaho isn't all spuds and movies. There's more pioneer history than you can poke a stick at. In the mid-1800s, over 50,000 people crossed the state on their way to Oregon's Willamette Valley.

But Idaho isn't all spuds and movies. There's more pioneer history than you can poke a stick at. In the mid-1800s, over 50,000 people crossed the state on their way to Oregon's Willamette Valley.From Fort Hall (near Blackfoot) in eastern Idaho, the Oregon Trail followed the Snake River west on a relatively easy track. But it wasn't the most direct route, swinging south in a shallow curve before heading north again to what was then called Fort Boise. Ferry owner John Jeffrey encouraged the wagon trains to cross at the Blackfoot River (on his ferry, naturally) and travel a shorter route along a trail traditionally used by the Shoshone people.

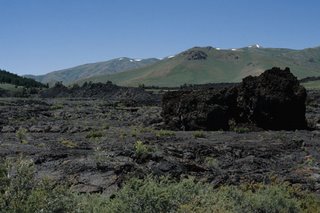

In 1862, a massive wagon train led by guide Tim Goodale travelled along the straight track, which became known as Goodale's Cutoff. From then on, this was the route taken by most of the settlers, who were afraid of the increasing resistance by the Shoshone and Bannock people along the Snake River. But although it was a more direct route, it passed across the northern edge of a massive lava flow. Not only did the jagged surface slow down the wagons but the summer heat desiccated the wood of their wheels and frames. They fell apart as they crossed the flow.

In 1862, a massive wagon train led by guide Tim Goodale travelled along the straight track, which became known as Goodale's Cutoff. From then on, this was the route taken by most of the settlers, who were afraid of the increasing resistance by the Shoshone and Bannock people along the Snake River. But although it was a more direct route, it passed across the northern edge of a massive lava flow. Not only did the jagged surface slow down the wagons but the summer heat desiccated the wood of their wheels and frames. They fell apart as they crossed the flow. Even without the wagons, that lava flow (now part of the Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve) is tough going. Like all flows, it's hot and desolate. Yet there is no great volcano. Nothing like Mount St Helens or Augustine. Here, lava welled up along the Great Rift, an 80km fracture zone that split the earth.

Even without the wagons, that lava flow (now part of the Craters of the Moon National Monument and Preserve) is tough going. Like all flows, it's hot and desolate. Yet there is no great volcano. Nothing like Mount St Helens or Augustine. Here, lava welled up along the Great Rift, an 80km fracture zone that split the earth. Much of the flow is less than 15,000 years old—some of it less than 2,000 years old—cinder black and sharp as shark's teeth. Even in summer, snow persists deep inside the largest cinder cones, insulated from the sun by the dense walls.

Much of the flow is less than 15,000 years old—some of it less than 2,000 years old—cinder black and sharp as shark's teeth. Even in summer, snow persists deep inside the largest cinder cones, insulated from the sun by the dense walls.