When I lived in North Queensland all those years ago, I put up with the cockroaches, even though they're so big that I'd get up in the morning to find they'd rearranged the furniture during their nocturnal wanderings. The bastards.

Anyway, since returning to Melbourne, where the only cockroaches I've seen have been native ones, I've become re-sensitised to the introduced Periplaneta. So when I went up to Lake Eacham last year, I wasn't prepared to share my space with them. I dealt with the first few incursions by catching the insects in a jar and chucking them out. But that generosity didn't last. When one of the buggers crawled across the carpet in broad daylight, I cracked. And so did the cockroach. Under my shoe.

Now I had a dismantled cockroach to deal with. As I watched, it started to writhe in just the way that dead insects shouldn't. But even live cockroaches don't writhe. And they certainly don't uncoil like a watch spring.

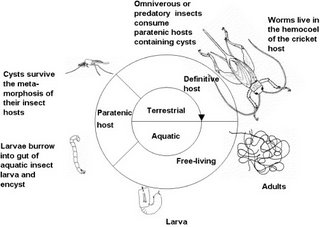

The cockroach was moving around by day because it was infected with two nematomorphan worms. The worms develop inside an insect or arachnid host, getting bigger and bigger until they are ready to emerge. But the adult worms are aquatic and the hosts terrestrial. They solve the problem by making their hosts seek out water. Once there, the worms emerge in a rather less dramatic way than the Alien but with much the same consequences. Mermithid nematodes manipulate their hosts in a similar manner.

Of course, a worm can lead a host to water but it must also make it think ... that it can swim. That's the key. Nematomorphans will not (or cannot) emerge until the host is immersed. But most insects won't voluntarily take a dip. So the worm has to encourage its host to fling itself lemming-like into the nearest pond, puddle, swimming pool or toilet.

How do they do it?

We still don't know the exact mechanism but there is evidence that they can manipulate the amount of neurotransmitters in the host's nervous system and increase the production of its nerve cells. That sort of disruption to a brain can only end badly.

So here we have it. An insect, driven mad by the worm inside, is forced to commit suicide but is ripped apart before it can drown ... Ain't nature wonderful?

The Neurophilosopher's Blog has a post on these (and other) mind-controlling organisms. There's also some beaut video footage.

And you know what, I hadn't read that blog before I prepared this post. Now I'm wondering whether we've both succumbed to the wiles of a brain-storming parasite ...

(Oh, you should know that I scooped up the worms from the carpet and put them in a plastic bag filled with water, so I could release them in a nearby creek. But they didn't survive.)

______

Images from Hanelt et al.

Top: Natural life cycle of Paragordius varius (modified from Hanelt & Janovy, 2004)

Bottom: Water-seeking behaviour of a field cricket Nemobius sylvestris followed by the emergence of the hair-worm Paragordius tricupidatus.

Reference

Hanelt, B., Thomas, F. & Schmidt-Rhaesa, A. (2005). Biology of the phylum Nematomorpha. Advances in Parasitology 59: 244 – 305 (+ plates)