Right. The gate man has left for the day (he'll be back tomorrow), I have switched off the radio, brewed the coffee and am about to unplug the spawn-of-the-devil internet cable. Nothing is going to stop me from knocking off another 500+ words on draft number wotsit. Three? Four? Whatever.

I'll be back next month. (Which, incidentally, is when the NaNoWriMo folks start registration for National Novel Writing Month. Sort of. They say around October 1.)

An occasional blog about natural history, travel, books and writing ... and anything else that catches my attention.

Saturday 30 September 2006

Big trees

Reuters reports:

A redwood tree discovered in a remote California forest has turned out to be the world's tallest tree, edging out one nearby that had been the previous titleholder, a botanist said on Friday.

Humboldt State University Professor Steve Sillett told Reuters the record-setting tree, named Hyperion, is 379.1 feet (115.5 metres) tall, besting the previous record holder, the 370.5-foot(112.9 metre)-tall Stratosphere Giant.

Researchers exploring remote and rugged terrain this summer in the Redwood National and State Parks along California's northernmost coast also discovered two other redwoods taller than the Stratosphere Giant, suggesting there had been many more massive ancient redwoods in the area, Sillett said.

A redwood tree discovered in a remote California forest has turned out to be the world's tallest tree, edging out one nearby that had been the previous titleholder, a botanist said on Friday.

Humboldt State University Professor Steve Sillett told Reuters the record-setting tree, named Hyperion, is 379.1 feet (115.5 metres) tall, besting the previous record holder, the 370.5-foot(112.9 metre)-tall Stratosphere Giant.

Researchers exploring remote and rugged terrain this summer in the Redwood National and State Parks along California's northernmost coast also discovered two other redwoods taller than the Stratosphere Giant, suggesting there had been many more massive ancient redwoods in the area, Sillett said.

Universities are good for biodiversity

Daniel Moerman and George Estabrook from the University of Michigan (at Dearborn and Ann Arbor respectively) compared the number of flowering plant species in university counties with the diversity in neighbouring counties. What they found was that almost every university was slap bang in the middle of a high diversity site, whereas surrounding areas were impoverished. Of the 37 institutions studied, only six missed the top spot, their species diversity exceeded by adjacent counties. (They all made second place, except for the University of Washington, which came in third in its location.)

The pattern also holds true for snails. Research at a snail's pace has tallied the records for that state and found that the highest diversity occurs in counties containing universities. (Nine counties reported NO snail species at all. What the ...?)

So what's the deal? Are universities typically built in areas of high biodiversity? Are they over-run by exotic species, which might bump up the records? Or are the university counties bigger? Does size account for the higher number?

Or is it because universities have a greater density of biologists than the surrounding counties? And those botanists and malacologists (in these cases) concentrate on the immediate area.

Which answer do you favour?

C'mon, people, get off your arses and look further than the end of the campus road.

Read more

Moerman, D.E. & Estabrook, G.F. (2006). The botanist effect: counties with maximal secies richness tend to be home to universities and botanists. Journal of Biogeography (in press)

The pattern also holds true for snails. Research at a snail's pace has tallied the records for that state and found that the highest diversity occurs in counties containing universities. (Nine counties reported NO snail species at all. What the ...?)

So what's the deal? Are universities typically built in areas of high biodiversity? Are they over-run by exotic species, which might bump up the records? Or are the university counties bigger? Does size account for the higher number?

Or is it because universities have a greater density of biologists than the surrounding counties? And those botanists and malacologists (in these cases) concentrate on the immediate area.

Which answer do you favour?

C'mon, people, get off your arses and look further than the end of the campus road.

Read more

Moerman, D.E. & Estabrook, G.F. (2006). The botanist effect: counties with maximal secies richness tend to be home to universities and botanists. Journal of Biogeography (in press)

The first sign of spring

You know that spring has sprung in Melbourne when the skywriting planes take to the air. I'm a sucker for this sort of aerobatics.

Last year, the most popular sky-written slogan was 'Woo hoo!', which advertised a car manufacturer. So successfully that I've completely forgotten which one. That worked.

Last year, the most popular sky-written slogan was 'Woo hoo!', which advertised a car manufacturer. So successfully that I've completely forgotten which one. That worked.

The (Grand) Final countdown

What I'm listening to as I write this: Try whistling this by Neil Finn.

Nice planning on Richard Stubb's radio show yesterday. While interviewing a member of the St John's Ambulance Service he suggested a visit to Crac des Chevalier as part of their training programme and then played Mark Seymour's Holy Grail. This won't make sense to anyone outside Australia, but the St John's Ambulance will be attending the AFL Grand Final, the theme song of which is ... You get the picture. It was funny at the time.

Yes, it's Grand Final Day. Apparently. The neighbours two doors up have their mates around. I saw eskies and cartons being unloaded from car boots this morning. Plenty of them. But now the lads are sitting in the back yard listening to Enya and Everclear. Those cartons must have been full of Fanta.

Otherwise, the game isn't very big in this street. The Vietnamese neighbours aren't interested. The Indian students across the road love cricket. (There's usually a game each evening. Luckily, they use a tennis ball rather than the real thing.) Of the few footy fans, my immediate neighbour barracks for St Kilda and the one diagonally opposite is a die-hard Bulldogs supporter. I'm not even sure the Fanta-swillers support either of the competing teams*. I think they're just looking for an excuse to get together and knock back fizzy drinks.

The Builder of Gates has turned up and is about to rip the old one off its hinges. This won't take a great deal of effort. Gravity should do it on its own. At some point my side path will be as well defended as Crac des Chevalier.

________________

*I'm not even sure who's playing. Sydney vs West Coast? Something like that. However, 95,000 people have jammed themselves into the MCG to watch the game, so I may well be in the minority. (But not in this street.)

Nice planning on Richard Stubb's radio show yesterday. While interviewing a member of the St John's Ambulance Service he suggested a visit to Crac des Chevalier as part of their training programme and then played Mark Seymour's Holy Grail. This won't make sense to anyone outside Australia, but the St John's Ambulance will be attending the AFL Grand Final, the theme song of which is ... You get the picture. It was funny at the time.

Yes, it's Grand Final Day. Apparently. The neighbours two doors up have their mates around. I saw eskies and cartons being unloaded from car boots this morning. Plenty of them. But now the lads are sitting in the back yard listening to Enya and Everclear. Those cartons must have been full of Fanta.

Otherwise, the game isn't very big in this street. The Vietnamese neighbours aren't interested. The Indian students across the road love cricket. (There's usually a game each evening. Luckily, they use a tennis ball rather than the real thing.) Of the few footy fans, my immediate neighbour barracks for St Kilda and the one diagonally opposite is a die-hard Bulldogs supporter. I'm not even sure the Fanta-swillers support either of the competing teams*. I think they're just looking for an excuse to get together and knock back fizzy drinks.

The Builder of Gates has turned up and is about to rip the old one off its hinges. This won't take a great deal of effort. Gravity should do it on its own. At some point my side path will be as well defended as Crac des Chevalier.

________________

*I'm not even sure who's playing. Sydney vs West Coast? Something like that. However, 95,000 people have jammed themselves into the MCG to watch the game, so I may well be in the minority. (But not in this street.)

Friday 29 September 2006

Apocalypse—now!

Cinema has never dealt satisfactorily with the end of the world. There's a passable bunch of science fiction films exploring humanity's destruction through pestilence, alien invasion, economic and/or ecological collapse or as the fly on the windscreen of a passing asteroid. All entertaining movies. But no one has made a good film about the Apocalypse. I'm talking Four Horsemen, seal-opening, star called Wormwood, trumpet-sounding, ooh, ooh, I'm covered in boils stuff.

There's excellent source material—the Book of Revelation, written by John who had clearly spent too much time on his own on Patmos*. Not much of a narrative but a bundle of great visuals. Stick in a bit of Hieronymus Bosch and you're laughing. (Although probably not too loudly and¬—if you look like one of Bosch's creations—on the other side of your face. Literally.)

Of course, a few film makers have already mined the Apocalyptic lode but none of them struck it rich.

Here's a (non-exhaustive) list of those movies with their taglines. Obviously, it pays to have a sense of the absurd ...

The Omen (1976)

Our final warning.

The Omen II (1978)

The first time was only a warning.

(Eh? Oh, I get it.)

The Omen III (1981)

The power of evil is no longer in the hands of a child.

(It's in the hands of Sam Neill. The Apocalypse, we were meant to precipitate it.)

The Omen (2006)

His day will come.

(Enough already!)

The Seventh Sign (1988)

The seals have been broken. The prophecies have begun. Now only one woman can halt the end of our world.

(And it's Demi Moore. Who'd have thought it?)

The Stand (1994)

The end of the world is just the beginning.

The Prophecy (1995)

There is a war in heaven and all hell is about to break loose.

(I quite enjoyed this one. Mainly because Christopher Walken played Gabriel and Viggo Mortensen played Lucifer. They gave the Apocalypse a bit of verve.)

End of Days (1999)

Prepare for the end.

(... with Gabriel Byrne as Satan and Arnie as Jericho Kane, the saviour of the world. Yep. He'll be back.)

_________________________

*He's not the only one with too much time on his hands.

There's excellent source material—the Book of Revelation, written by John who had clearly spent too much time on his own on Patmos*. Not much of a narrative but a bundle of great visuals. Stick in a bit of Hieronymus Bosch and you're laughing. (Although probably not too loudly and¬—if you look like one of Bosch's creations—on the other side of your face. Literally.)

Of course, a few film makers have already mined the Apocalyptic lode but none of them struck it rich.

Here's a (non-exhaustive) list of those movies with their taglines. Obviously, it pays to have a sense of the absurd ...

The Omen (1976)

Our final warning.

The Omen II (1978)

The first time was only a warning.

(Eh? Oh, I get it.)

The Omen III (1981)

The power of evil is no longer in the hands of a child.

(It's in the hands of Sam Neill. The Apocalypse, we were meant to precipitate it.)

The Omen (2006)

His day will come.

(Enough already!)

The Seventh Sign (1988)

The seals have been broken. The prophecies have begun. Now only one woman can halt the end of our world.

(And it's Demi Moore. Who'd have thought it?)

The Stand (1994)

The end of the world is just the beginning.

The Prophecy (1995)

There is a war in heaven and all hell is about to break loose.

(I quite enjoyed this one. Mainly because Christopher Walken played Gabriel and Viggo Mortensen played Lucifer. They gave the Apocalypse a bit of verve.)

End of Days (1999)

Prepare for the end.

(... with Gabriel Byrne as Satan and Arnie as Jericho Kane, the saviour of the world. Yep. He'll be back.)

_________________________

*He's not the only one with too much time on his hands.

Grebe expectations

If anyone's looking for the Australasian grebe I mentioned on Ben Cruachan Blog, it's here.

And this is a grebe I photographed a couple of weeks ago at Hastie's Swamp, near Atherton in Far North Queensland. This one could stay underwater for so long, I thought it might be wearing an aqualung.

And this is a grebe I photographed a couple of weeks ago at Hastie's Swamp, near Atherton in Far North Queensland. This one could stay underwater for so long, I thought it might be wearing an aqualung.

And this is a grebe I photographed a couple of weeks ago at Hastie's Swamp, near Atherton in Far North Queensland. This one could stay underwater for so long, I thought it might be wearing an aqualung.

And this is a grebe I photographed a couple of weeks ago at Hastie's Swamp, near Atherton in Far North Queensland. This one could stay underwater for so long, I thought it might be wearing an aqualung.

Jaws on land

Meet Dysdera crocata. My garden is full of them. They're growing fat on the slaters that cluster under stones and timber.

Meet Dysdera crocata. My garden is full of them. They're growing fat on the slaters that cluster under stones and timber.The family is native to southern and eastern Europe (including the Canary Islands), the Middle East and North Africa. (A couple of species also occur in South America—an interesting biogeographical conundrum.) Of the numerous species, only Dysdera crocata has been transported around the world. It is now established in suitable habitats in other parts of Europe, in North America and Australia. (When first collected in Australia, it was thought to be a native species and given the name Dysdera australiensis. It wasn't until the 1960s that someone spotted the anomaly and identified it correctly.)

In Australia, Dysdera crocata appears to be restricted to the south-eastern region. That may be due to under-reporting because its not a very outgoing species. It lives in damp locations under logs, rocks and garden refuse. Although it doesn't catch its prey in a web, Dysdera spins a sac-like retreat. This specimen is emerging from its retreat and is not happy about the camera.

In Australia, Dysdera crocata appears to be restricted to the south-eastern region. That may be due to under-reporting because its not a very outgoing species. It lives in damp locations under logs, rocks and garden refuse. Although it doesn't catch its prey in a web, Dysdera spins a sac-like retreat. This specimen is emerging from its retreat and is not happy about the camera.Dysdera tends to scuttle away when disturbed but occasionally gets shirty when threatened. The jaws are long and powerful enough to penetrate the exoskeleton of a slater, so they can pierce human skin with ease. The combination of stroppiness and strength make this spider something to avoid. But if you do get bitten, there's no need to panic.

Vetter noted that it was repeatedly misidentified in the U.S. as the dangerous brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa). When he looked at the records in detail, he found only eight verifiable bites. All of them resulted in local and short-lived effects. In one case, the patient also reported systemic effects—nausea, dizziness and lethargy but these did not persist. There was no necrosis (tissue death).

Vetter noted that it was repeatedly misidentified in the U.S. as the dangerous brown recluse spider (Loxosceles reclusa). When he looked at the records in detail, he found only eight verifiable bites. All of them resulted in local and short-lived effects. In one case, the patient also reported systemic effects—nausea, dizziness and lethargy but these did not persist. There was no necrosis (tissue death).(I was bitten by a huntsman spider some months ago and that was much worse. Only local effects but they lasted for quite a while. The story of how I got bitten is a long and daft one, which will only confirm that I really need to be in some sort of home for the feeble-minded. On the other hand, the story of how I got stung by a little marbled scorpion, Lychas marmoreus, demonstrates that shit really can happen. It was on a towel at a B & B. What are the odds?)

Read more

Vetter, R.S. & Isbister, G.K. (2006). Verified bites by the woodlouse spider, Dysdera crocata. Toxicon 47: 826–829.

Worse than a Vogon

Today is the 104th anniversary of the death of William Topaz McGonagall, author of some truly awful poetry. (For another creator of dreadful verse, see this post about the cheese-obsessed James McIntyre.)

Perhaps McGonagall's most famous poem is The Tay Bridge Disaster, which commemorates, in forced rhyme and laboured meter, the collapse of the Tay Bridge and the death of dozens of train passengers.

The poem opens with:

And closes with:

McGonagall also fancied himself as a bit of a song-writer too.

While McGonagall was belting out this rollicking tune in a pub, the landlord pelted him with food. In his autobiography, the poet refers to the landlord as 'the first man who threw peas at me'. It must have become a common occurrence in his life. And not without reason.

There's a fine selection of his poems on the McGonagall Online site. I will close with his work commemorating Alfred, Lord Tennyson. On the Poet Laureate's death, McGonagall tried to petition Queen Victoria to make him Tennyson's successor. Luckily, the Queen was not in residence when he arrived at Balmoral. At least, that's what they told him.

Perhaps McGonagall's most famous poem is The Tay Bridge Disaster, which commemorates, in forced rhyme and laboured meter, the collapse of the Tay Bridge and the death of dozens of train passengers.

The poem opens with:

Beautiful Railway Bridge of the Silv'ry Tay!

Alas! I am very sorry to say

That ninety lives have been taken away

On the last Sabbath day of 1879,

Which will be remember'd for a very long time.

And closes with:

It must have been an awful sight,

To witness in the dusky moonlight,

While the Storm Fiend did laugh, and angry did bray,

Along the Railway Bridge of the Silv'ry Tay,

Oh! ill-fated Bridge of the Silv'ry Tay,

I must now conclude my lay

By telling the world fearlessly without the least dismay,

That your central girders would not have given way,

At least many sensible men do say,

Had they been supported on each side with buttresses,

At least many sensible men confesses,

For the stronger we our houses do build,

The less chance we have of being killed.

McGonagall also fancied himself as a bit of a song-writer too.

I'm a rattling boy from Dublin town,

I courted a girl called Biddy Brown,

Her eyes they were as black as sloes,

She had black hair and an aquiline nose.

Chorus

Whack fal de da, fal de darelido,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelay,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelido,

Whack fal de da, fal de darelay.

While McGonagall was belting out this rollicking tune in a pub, the landlord pelted him with food. In his autobiography, the poet refers to the landlord as 'the first man who threw peas at me'. It must have become a common occurrence in his life. And not without reason.

There's a fine selection of his poems on the McGonagall Online site. I will close with his work commemorating Alfred, Lord Tennyson. On the Poet Laureate's death, McGonagall tried to petition Queen Victoria to make him Tennyson's successor. Luckily, the Queen was not in residence when he arrived at Balmoral. At least, that's what they told him.

Death and Burial of Lord Tennyson

Alas! England now mourns for her poet that's gone—

The late and the good Lord Tennyson.

I hope his soul has fled to heaven above,

Where there is everlasting joy and love.

He was a man that didn't care for company,

Because company interfered with his study,

And confused the bright ideas in his brain,

And for that reason from company he liked to abstain.

He has written some fine pieces of poetry in his time,

Especially the May Queen, which is really sublime;

Also the gallant charge of the Light Brigade—

A most heroic poem, and beautifully made.

…

And, in conclusion, I most earnestly pray,

That the people will erect a monument for him without delay,

To commemorate the good work he has done,

And his name in gold letters written thereon!

Thursday 28 September 2006

Embryos are cool

Evolutionary biologist, PZ Myers, filmed the development of a zebrafish embryo. He used time-lapse photography, reducing 18 hours of cell division and differentiation into less than a minute of vision. You can read more about the process and a whole bunch of other entertaining and thought-provoking stuff at Pharyngula.

If you haven't had your fill of the amazing biological process that turns something as simple as this into a complex organism, then check out David Nelson's photographic log of frog development. It's updated regularly.

If you haven't had your fill of the amazing biological process that turns something as simple as this into a complex organism, then check out David Nelson's photographic log of frog development. It's updated regularly.

Irvinebank

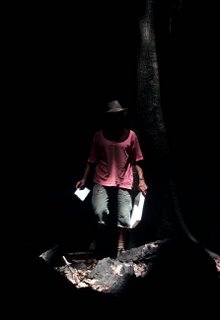

I hadn't been to Irvinebank for about 15 years. The last time I was there, I'd been on a field trip to the limestone caves at Chillagoe – Mungana National Park. My b/f at the time and I had been looking at the small scale distribution of limestone-associated microsnails. We never got around to publishing the work. (Just to prove we did something, here's his lordship at the study site.)

I hadn't been to Irvinebank for about 15 years. The last time I was there, I'd been on a field trip to the limestone caves at Chillagoe – Mungana National Park. My b/f at the time and I had been looking at the small scale distribution of limestone-associated microsnails. We never got around to publishing the work. (Just to prove we did something, here's his lordship at the study site.)But I digress.

Irvinebank is about 30 kilometres west of Herberton on a well-made, picturesque gravel road. (A well-made, picturesque gravel road with a very, very soft shoulder, as I discovered when I stopped to take a photograph of the flowering Grevillea pteridifolia.)

The town has a population of 85, which makes it a metropolis compared with neighbouring Watsonville. There's a pub and a few other things. But let's face it, if the town's got a pub, the locals don't need much else.

The town has a population of 85, which makes it a metropolis compared with neighbouring Watsonville. There's a pub and a few other things. But let's face it, if the town's got a pub, the locals don't need much else. Irvinebank is an old tin-mining area. Following the discovery of tin at Herberton, miners scoured the region for other sources, both lode and alluvial. Magnate John Moffat moved his business to Irvinebank, where he established a smelter to process the metal. Moffat's home—the oldest two-storey building in North Queensland—is now the Loudoun House Museum.

Irvinebank is an old tin-mining area. Following the discovery of tin at Herberton, miners scoured the region for other sources, both lode and alluvial. Magnate John Moffat moved his business to Irvinebank, where he established a smelter to process the metal. Moffat's home—the oldest two-storey building in North Queensland—is now the Loudoun House Museum. For a while, the town was a lively community. The School of the Arts, opened on Boxing Day 1900, kept the locals entertained. Among the amusements were shadow pantomimes, euphonium recitals and plays, including a dramatic sketch entitled 'A pair of lunatics'. X-rays were also a popular distraction. One show was described as a 'short lecture and practical demonstration, showing the bones of the hand, the contents of satchels and purses, and other mysterious effects.' The Walsh & Tinaroo Miner, which must have been the Sun of its day, said the show was 'most x-traordinary'.

For a while, the town was a lively community. The School of the Arts, opened on Boxing Day 1900, kept the locals entertained. Among the amusements were shadow pantomimes, euphonium recitals and plays, including a dramatic sketch entitled 'A pair of lunatics'. X-rays were also a popular distraction. One show was described as a 'short lecture and practical demonstration, showing the bones of the hand, the contents of satchels and purses, and other mysterious effects.' The Walsh & Tinaroo Miner, which must have been the Sun of its day, said the show was 'most x-traordinary'.  Like Herberton, the town attracted a succession of fascinating people. Dr Thomas Bancroft, resident medical officer at Stannary Hills in the early 1900s, worked on hookworm and dengue mosquitoes. He also collected plant specimens for the office of the colonial botanist. Dr William Evan MacFarlane, who took charge of the Walsh District Hospital at Irvinebank in 1906, built an observatory next to his house.

Like Herberton, the town attracted a succession of fascinating people. Dr Thomas Bancroft, resident medical officer at Stannary Hills in the early 1900s, worked on hookworm and dengue mosquitoes. He also collected plant specimens for the office of the colonial botanist. Dr William Evan MacFarlane, who took charge of the Walsh District Hospital at Irvinebank in 1906, built an observatory next to his house.Irvinebank is no longer the centre of the tin industry. But many of the buildings remain. I didn't spend long enough exploring the mining legacy. I will go back. It's too good to miss.

Beware of the ...

I'm going to collect warning signs from around the country. Not literally. I have no plans to rip them off their posts and jam them into the boot of the car, whistling nonchalantly all the while. I mean with the camera.

I'm going to collect warning signs from around the country. Not literally. I have no plans to rip them off their posts and jam them into the boot of the car, whistling nonchalantly all the while. I mean with the camera.The cassowary signs are all over the place. It's not that much of a challenge getting a photograph of one of these. (It's a bit more of a challenge getting a photo while avoiding the speeding traffic.) I took this picture near Bramston Beach.

Even more abundant on the coastal plain are the signs warning visitors of estuarine crocodiles. This one was beside the track to Eubenangee Swamp. Not that you'd want to swim in the Alice River.

Even more abundant on the coastal plain are the signs warning visitors of estuarine crocodiles. This one was beside the track to Eubenangee Swamp. Not that you'd want to swim in the Alice River.The sign I really wanted to photograph featured a tree kangaroo. As was the case with cassowary and chick, the tree kangaroo was rendered as something of a mutant. A bit like a ground sloth with a tail. Although there are a few examples along the Malanda – Millaa Millaa road, I couldn't find a good spot to stop. When I did locate a site, some bugger of a cop set up a radar trap on it. I could have asked him to move but I thought that I might just leave him to it.

(Last time I saw mobile speed radar in FNQ, the cop in charge had enclosed the whole unit in a plastic bag to keep off the rain . I guess it minimised the paperwork.)

It’d never happen here

Staff at the University of Bergen in Norway are not afraid to point out the good and the bad at their institution.

Good on her! The article, Frustrated by poor lecturing conditions, appears in the 28 September edition of På Høyden, the university newsletter.

Imagine that, people—an institute of higher education that takes these thing seriously.

Professor of biology Karin Pittman reached the end of her rope last week when she had to welcome 60 new master's degree students in an auditorium at the Høyteknologisenteret building with PCs and projectors that were not in working order. Nor was there any chalk, and the tattered sponge was mouldy. The room was also partially filled with empty cardboard boxes.

“These are undignified conditions for both lecturers and students alike. I have pointed out many times before that the state of the auditoriums is substandard and coordination between the different parties responsible for such matters is not good enough. It is a shame that nothing is being done about it,” says Professor Pittman, who, in an e-mail to the faculty administration, has warned that she will go on strike if conditions are not improved.

Good on her! The article, Frustrated by poor lecturing conditions, appears in the 28 September edition of På Høyden, the university newsletter.

Imagine that, people—an institute of higher education that takes these thing seriously.

Wednesday 27 September 2006

Dead bears

I'm reading a recently-published novel, the title and author of which I won't mention. It's a bit strange. Not least of all because one of the characters announces that 'Everybody loves a grizzly corpse.'

Perhaps I should report this to the RSPCA.

Perhaps I should report this to the RSPCA.

Begin the Barrine

Eacham and Barrine are maars, lakes formed when groundwater met magma between two million and 100,000 years ago. The resulting explosions of steam blew out enormous craters in the granite. Although Barrine has a larger surface area than Eacham, both lakes are of roughly the same depth—between 65 and 70 metres.

Eacham and Barrine are maars, lakes formed when groundwater met magma between two million and 100,000 years ago. The resulting explosions of steam blew out enormous craters in the granite. Although Barrine has a larger surface area than Eacham, both lakes are of roughly the same depth—between 65 and 70 metres.Recognised for their natural and recreational significance since the late 1800s, the two lakes were gazetted as national parks in 1934 and amalgamated into the Crater Lakes NP in 1994.

But before all that, George and Margaret Curry constructed a recreational hall on the northern shore in 1926. The building became a guest house, then a convalescent home for the Army during WWII, before becoming a tea house. The Curry family's home-baked scones have won prizes. And for good reason.

But before all that, George and Margaret Curry constructed a recreational hall on the northern shore in 1926. The building became a guest house, then a convalescent home for the Army during WWII, before becoming a tea house. The Curry family's home-baked scones have won prizes. And for good reason.Lake Barrine is a great spot for watching wildlife. A narrow, well-made path circles the lake, threading through rainforest and giving visitors a great opportunity to see many unusual species.

The first stop on a clockwise peregrination is at the twin kauris. Kauri pines (Agathis microstachya) are endemic to the Atherton Tablelands. These two on the edge of Lake Barrine are about 40 metres in height. They’re reported to be the tallest conifers in the country. Other Agathis species occur in New Zealand, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, New Guinea, Borneo and the Philippines.

The first stop on a clockwise peregrination is at the twin kauris. Kauri pines (Agathis microstachya) are endemic to the Atherton Tablelands. These two on the edge of Lake Barrine are about 40 metres in height. They’re reported to be the tallest conifers in the country. Other Agathis species occur in New Zealand, Vanuatu, New Caledonia, New Guinea, Borneo and the Philippines. Musky rat kangaroos forage by day among the leaf litter. You'll certainly hear them scuttling about, even if the only glimpse you get is of a furry, russet-coloured bum disappearing into the undergrowth. Tooth-billed bowerbirds and grey-headed robins (right) are abundant. At certain times of the day, spotted tree monitors bask on fallen timber. In the wet season, orange-footed scrub fowl rake over the litter. For the rest of the year, you'll have to wade knee-deep through flocks of brush turkeys.

Musky rat kangaroos forage by day among the leaf litter. You'll certainly hear them scuttling about, even if the only glimpse you get is of a furry, russet-coloured bum disappearing into the undergrowth. Tooth-billed bowerbirds and grey-headed robins (right) are abundant. At certain times of the day, spotted tree monitors bask on fallen timber. In the wet season, orange-footed scrub fowl rake over the litter. For the rest of the year, you'll have to wade knee-deep through flocks of brush turkeys.The lake’s popularity isn’t merely confined to tourists and bird-watchers. After a morning of shovelling award-winning Devonshire teas into our faces, a friend and I decided to go for a stroll. We hadn’t even got as far as the start of the path when we encountered a strange happening.

A small number of people were standing in waist deep water, addressing a rather larger bunch of people on the shore. It was an odd sight, so my pattern-seeking brain tried to match it up to something already filed away in there.

Aha! I thought. It must be an aquatic ecology class.

Luckily, I didn’t mention this. And the next thing my brain flicked out of my mental filing cabinet was … a baptism.

As we drew level with the group, a young girl (she looked about eight years old) entered the water, which was almost up to her shoulders. After a few quiet words from one very soggy chap, she allowed him to immerse her in the lake. When she emerged, the crowd gave her a round of applause.

That's Queensland.

Blog labels

I'm putting labels on my posts so anyone interested can pull up all the posts on a particular topic. I haven't got very far. Consider it a work in progress.

(I was going to use the label 'rants' for some posts but have opted for the less accurate 'musings' because it's more genteel. And that's me. Terribly well-bred.)

(I was going to use the label 'rants' for some posts but have opted for the less accurate 'musings' because it's more genteel. And that's me. Terribly well-bred.)

Tuesday 26 September 2006

I've just had one of those conversations where neither contributor could remember anything in detail but between the vague recollections and incomplete sentences we managed to cover the topic (English playwrights and actors of the 20th century) adequately.

This made me think about producing a dichotomous key for use on such occasions. Something along the lines of:

1. That man, you know the one, he:

2. You know, the play set in:

3. You remember the actor. Yes, you do.

You get the idea ...

This made me think about producing a dichotomous key for use on such occasions. Something along the lines of:

1. That man, you know the one, he:

- wrote that play (go to 2)

- was in that play (go to 3)

2. You know, the play set in:

- northern England (got to 4)

- London or the south (go to 5)

3. You remember the actor. Yes, you do.

- He's dead (go to 6)

- He's still alive (got to 7)

You get the idea ...

Close encounters of the turd kind

Whose poo is this? It's an easy one, so there's no prize. I took the photograph in the car park of the Gadgarra Cedar National Park.

Whose poo is this? It's an easy one, so there's no prize. I took the photograph in the car park of the Gadgarra Cedar National Park.(If you're ... er ... stuck, the answer's in the file name. Just click on the picture.)

I'm baaaack

And had the exit at Tullamarine's long term carpark been better signposted, I would have been home earlier. About 40 minutes earlier. (Although some of that delay was due to me trying to find my car, which I hadn't actually left in J1 ...)

Circus of the Spineless

Feast your eyes and feed your mind on an exuberance of invertebrates at this month's carnival of critters at Deep Sea News.

There's something for everyone: sex, violence, ecological disasters. the great tapestry of life. And tattoos.

Circus of the Spineless: check it out now. You know you want to.

There's something for everyone: sex, violence, ecological disasters. the great tapestry of life. And tattoos.

Circus of the Spineless: check it out now. You know you want to.

Monday 25 September 2006

Sleeping on it

Here's something I thought I might mention before it slips my mind forever. Observant readers might have spotted that I'm a keen writer of both fiction and non-fiction. At the moment, I'm working up the third (or is it fourth?) draft of a novel, which I'm hoping to complete some time before Christmas. (I'm not saying which year.)

There are many differences between the first draft and the most recent version. You know the drill. Characters have been ditched, added, changed. Plot lines have been tightened until they hum in a high wind. Hackneyed metaphors have got the chop ... And I've rewritten passive sentences.

Anyway, a couple of things weren't working. One was the death of a character. Dramatic, sure, but not quite right. The solution came to me while I was wandering around a rainforest up north. I sat down on the wet path, risking leeches (bad) and scrub itch (worse), and scribbled down the entire scene in my notebook. Nothing to do with the surroundings. Everything to do with a refreshed mind.

The second problem was the denouement. Well, I didn't think it was too big a problem until I had a dream last night that played out a much sharper scene. Perfect! Now, all I have to do is relive that nightmare and I've got the conclusion.

There are many differences between the first draft and the most recent version. You know the drill. Characters have been ditched, added, changed. Plot lines have been tightened until they hum in a high wind. Hackneyed metaphors have got the chop ... And I've rewritten passive sentences.

Anyway, a couple of things weren't working. One was the death of a character. Dramatic, sure, but not quite right. The solution came to me while I was wandering around a rainforest up north. I sat down on the wet path, risking leeches (bad) and scrub itch (worse), and scribbled down the entire scene in my notebook. Nothing to do with the surroundings. Everything to do with a refreshed mind.

The second problem was the denouement. Well, I didn't think it was too big a problem until I had a dream last night that played out a much sharper scene. Perfect! Now, all I have to do is relive that nightmare and I've got the conclusion.

Limited blogging tonight

Apologies for the lack of pictures but no lack of ranting. I have a pile of stuff to get ready for tomorrow. When I have a bit more time (tomorrow evening, I hope), I'll put up some pictures of beautiful Lake Barrine on the Atherton Tablelands. A top spot.

Apologies for the lack of pictures but no lack of ranting. I have a pile of stuff to get ready for tomorrow. When I have a bit more time (tomorrow evening, I hope), I'll put up some pictures of beautiful Lake Barrine on the Atherton Tablelands. A top spot.In the meantime, here's a cute but utterly pointless shot of a sugar glider from Lake Eacham. They're common as sand flies up there, although much less likely to leave welts on your skin.

If you want to see more, David Nelson has an article and a short video of the sugar gliders at his place.

Sunday 24 September 2006

Mt Hypipamee: A big bang and an enigmatic snail

Although it looks like a crater, the 140-metre pit at Mt Hypipamee was blasted out of the granite by an explosion of volcanic gas. As the only diatreme in North Queensland, it is of great interest to geologists. What makes it even more unusual is that the surrounding area should be littered with granite blocks—after all, the bang took place less than three million years ago—but it isn't. Not a sausage. All that's left are pyroclastic basalts.

Although it looks like a crater, the 140-metre pit at Mt Hypipamee was blasted out of the granite by an explosion of volcanic gas. As the only diatreme in North Queensland, it is of great interest to geologists. What makes it even more unusual is that the surrounding area should be littered with granite blocks—after all, the bang took place less than three million years ago—but it isn't. Not a sausage. All that's left are pyroclastic basalts.  But it's not only the geology that's fascinating. The Crater is at a higher altitude than much of the Atherton Tablelands (1000 m), so its flora differs from that of nearby lakes Eacham and Barrine. The forest changes rapidly from typical tropical rainforest with figs and vines to wet eucalypt forest dominated by rose gums (Eucalyptus grandis).

But it's not only the geology that's fascinating. The Crater is at a higher altitude than much of the Atherton Tablelands (1000 m), so its flora differs from that of nearby lakes Eacham and Barrine. The forest changes rapidly from typical tropical rainforest with figs and vines to wet eucalypt forest dominated by rose gums (Eucalyptus grandis). Even more importantly, the national park is the type locality of a small and dull-looking snail—Craterodiscus pricei. Described by McMichael in 1959, this animal was shovelled in with the Helicarionidae and Camaenidae before being assigned to the Corillidae (sometimes called Plectopylidae). The last two moves were supported by a very, very small amount of evidence. In both cases, the decisions were based on the snail's lack of certain characteristics.

A large-scale molecular study has now placed Craterodiscus more or less back where it started. Plus ça change, plus c'est la même chose.

Read more about Corillidae in the great scheme of snail systematics

Wade, C.M., Mordan, P.B. & Naggs, F. (2006) Evolutionary relationships among the pulmonate land snails and slugs (Pulmonata: Stylommatophora). Biological Journal of the Linnean Society 87 (4): 593–610.

And about the Crater

Lava News (PDF)

Crossing the rubicunda

The great quantity of New Plants etc, Mr Banks and Dr Solander collected in this place occasioned my giving it the name Botany Bay.

Captain James Cook

Among the plants gathered at Botany Bay was this species, Kennedia rubicunda. The dingy coral pea is one of the few Kennedia to occur naturally on the east coast. Like many other species in the genus, it grows well in cultivation. Although spectacular, the flowers are diffult to spot among the foliage. The stalks are narrow and do not hold up the blooms. They disappear behind the triplets of leaves, which are so crisp and glossy they look as if they've been cut out of wrapping paper.

Among the plants gathered at Botany Bay was this species, Kennedia rubicunda. The dingy coral pea is one of the few Kennedia to occur naturally on the east coast. Like many other species in the genus, it grows well in cultivation. Although spectacular, the flowers are diffult to spot among the foliage. The stalks are narrow and do not hold up the blooms. They disappear behind the triplets of leaves, which are so crisp and glossy they look as if they've been cut out of wrapping paper. As a common name, 'dingy coral pea' does this plant a great disservice. The petals are as bright as those of the other red Kennedia species. What tones down the colour is the patch on the standard (the largest petal). In other red species, that patch is acid yellow. Even in this tiny K. microphylla the patch on the standard is obvious. But in K. rubicunda it is dusky pink. There's little contrast to our eyes. But the flowers aren't there for human entertainment. The flowers are for the benefit of pollinating insects or birds, which see colours in ways that we cannot.

As a common name, 'dingy coral pea' does this plant a great disservice. The petals are as bright as those of the other red Kennedia species. What tones down the colour is the patch on the standard (the largest petal). In other red species, that patch is acid yellow. Even in this tiny K. microphylla the patch on the standard is obvious. But in K. rubicunda it is dusky pink. There's little contrast to our eyes. But the flowers aren't there for human entertainment. The flowers are for the benefit of pollinating insects or birds, which see colours in ways that we cannot.

Build gates story

Okay. I have an old gate, which is held in place by the bolt on one side and friction on the other. I'm worried that it will disintegrate with the next strong gust of wind in much the same way that a vampire dissolves when the sunlight hits it.

Okay. I have an old gate, which is held in place by the bolt on one side and friction on the other. I'm worried that it will disintegrate with the next strong gust of wind in much the same way that a vampire dissolves when the sunlight hits it. I'd like to say that it's provided fine service. It hasn't: it's been crap. The previous owner constructed it but carpentry wasn't on his list of skills. As it's not on mine either, I've had to rely on the mysterious gate man.

So I have a new gate, which is so sturdy that it would resist a cavalry charge. That it remains unpainted and is lying on its side on my porch is of no consequence. One day that will change. One day I will have a huge, solid, all-opening, all-shutting, gleaming picket gate. Praise that day! Hallelujah!

So I have a new gate, which is so sturdy that it would resist a cavalry charge. That it remains unpainted and is lying on its side on my porch is of no consequence. One day that will change. One day I will have a huge, solid, all-opening, all-shutting, gleaming picket gate. Praise that day! Hallelujah!(Yeah, I know. Pickets. How naff. And how anachronistic. This is a house from 1922. But I'm not going to argue. I've got a gate.)

(I should point out that the wide-angle lens has caused distortion in both pictures. There's a touch of the carnival about this place but it's not quite the House of Fun.)

Saturday 23 September 2006

Tie me kangaroo apple down, sport

(This is an edited version of the original story. The confusion continues.)

For years, I've thought that the kangaroo apple dominating my back garden was Solanum laciniatum. But I'm notoriously bad at plant identification, so it really didn't surprise me when I found out that it could well be the closely-related S. aviculare.

Even real botanists get the two species confused. The only readily observable difference between them is in the colour of mature fruit. That of S. aviculare is ripe when it turns from green to orange. The fruit of S. laciniatum either remains green or pales to yellow-orange. Subtle differences, indeed.

Even real botanists get the two species confused. The only readily observable difference between them is in the colour of mature fruit. That of S. aviculare is ripe when it turns from green to orange. The fruit of S. laciniatum either remains green or pales to yellow-orange. Subtle differences, indeed.

Solanum aviculare occurs along the east coast of Australia, the New Guinea highlands and New Zealand. (It was described in 1786 from specimens collected earlier at Queen Charlotte Sound on Cook's second voyage down under.) Solanum laciniatum has a similar range and history. No wonder they're difficult to tell apart!

Odd things have happened in the evolution of S. aviculare and its closest relatives—S. laciniatum and the New Guinea endemic S. multivenosum. It's all to do with the number of chromosomes.

Most species have two sets of chromosomes—one set from each parent. This condition is called diploidy and is the 'normal' state. Solanum aviculare is a diploid species. But the other two are tetraploid: they have four sets of chromosomes.

It's been suggested that this condition has resulted from hybridisation between S. aviculare and the south-eastern Australian S. vescum, another diploid species. Although such hybrids inherit a single set of chromosomes from each parent (in this example, one set from S. aviculare and one from S. vescum), these chromosomes don't match up. This causes problems with reproduction—they can't divvy up the chromosomes properly to pass on to the next generation—so the two sets of chromosomes double in number. Each chromosome now has a partner to pass on.

It's been suggested that this condition has resulted from hybridisation between S. aviculare and the south-eastern Australian S. vescum, another diploid species. Although such hybrids inherit a single set of chromosomes from each parent (in this example, one set from S. aviculare and one from S. vescum), these chromosomes don't match up. This causes problems with reproduction—they can't divvy up the chromosomes properly to pass on to the next generation—so the two sets of chromosomes double in number. Each chromosome now has a partner to pass on.

It is also possible that the tetraploid species arose from spontaneous doubling of the normal chromosome complement. No inter-species shenanigans. It just happened.

Both scenarios are plausible. What we need now is a gel jock to sort out the conundrum.

For years, I've thought that the kangaroo apple dominating my back garden was Solanum laciniatum. But I'm notoriously bad at plant identification, so it really didn't surprise me when I found out that it could well be the closely-related S. aviculare.

Even real botanists get the two species confused. The only readily observable difference between them is in the colour of mature fruit. That of S. aviculare is ripe when it turns from green to orange. The fruit of S. laciniatum either remains green or pales to yellow-orange. Subtle differences, indeed.

Even real botanists get the two species confused. The only readily observable difference between them is in the colour of mature fruit. That of S. aviculare is ripe when it turns from green to orange. The fruit of S. laciniatum either remains green or pales to yellow-orange. Subtle differences, indeed.Solanum aviculare occurs along the east coast of Australia, the New Guinea highlands and New Zealand. (It was described in 1786 from specimens collected earlier at Queen Charlotte Sound on Cook's second voyage down under.) Solanum laciniatum has a similar range and history. No wonder they're difficult to tell apart!

Odd things have happened in the evolution of S. aviculare and its closest relatives—S. laciniatum and the New Guinea endemic S. multivenosum. It's all to do with the number of chromosomes.

Most species have two sets of chromosomes—one set from each parent. This condition is called diploidy and is the 'normal' state. Solanum aviculare is a diploid species. But the other two are tetraploid: they have four sets of chromosomes.

It's been suggested that this condition has resulted from hybridisation between S. aviculare and the south-eastern Australian S. vescum, another diploid species. Although such hybrids inherit a single set of chromosomes from each parent (in this example, one set from S. aviculare and one from S. vescum), these chromosomes don't match up. This causes problems with reproduction—they can't divvy up the chromosomes properly to pass on to the next generation—so the two sets of chromosomes double in number. Each chromosome now has a partner to pass on.

It's been suggested that this condition has resulted from hybridisation between S. aviculare and the south-eastern Australian S. vescum, another diploid species. Although such hybrids inherit a single set of chromosomes from each parent (in this example, one set from S. aviculare and one from S. vescum), these chromosomes don't match up. This causes problems with reproduction—they can't divvy up the chromosomes properly to pass on to the next generation—so the two sets of chromosomes double in number. Each chromosome now has a partner to pass on. It is also possible that the tetraploid species arose from spontaneous doubling of the normal chromosome complement. No inter-species shenanigans. It just happened.

Both scenarios are plausible. What we need now is a gel jock to sort out the conundrum.

More cheesy bits

On the subject of cheese-related monstrosities ... The Millaa Millaa Central Tablelands Co-operative Butter Association opened its factory in 1930. In the early 1970s, the association amalgamated with the Atherton Tablelands Dairy Association and started producing cheese. When the cheese making moved to Malanda, the historic building was turned into a second-hand goods shop. Now it's up for sale again.

On the subject of cheese-related monstrosities ... The Millaa Millaa Central Tablelands Co-operative Butter Association opened its factory in 1930. In the early 1970s, the association amalgamated with the Atherton Tablelands Dairy Association and started producing cheese. When the cheese making moved to Malanda, the historic building was turned into a second-hand goods shop. Now it's up for sale again.For goodness sake, someone buy it and restore it to its original colour.

Cheesy verse

And you thought William McGonagall was bad ...

James McIntyre was a Canadian poet who specialised in verse about cheese. Well, not just cheese. He had a fondness for other dairy products, all of which he celebrated in rhyme.

Born in Scotland in 1827, he emigrated to Ingersoll in Canada in 1841. He spend the rest of his long life there, penning stanzas in praise of cheese.

The Oxford County Library has an excellent site on McIntyre, including his obituary notice, which records that his poems 'were probably not of the highest literary standard'. You be the judge.

James McIntyre was a Canadian poet who specialised in verse about cheese. Well, not just cheese. He had a fondness for other dairy products, all of which he celebrated in rhyme.

Born in Scotland in 1827, he emigrated to Ingersoll in Canada in 1841. He spend the rest of his long life there, penning stanzas in praise of cheese.

The Oxford County Library has an excellent site on McIntyre, including his obituary notice, which records that his poems 'were probably not of the highest literary standard'. You be the judge.

Ode On the Mammoth Cheese

(weight over seven thousand pounds)

We have seen thee, queen of cheese,

Lying quietly at your ease,

Gently fanned by evening breeze,

Thy fair form no flies dare seize.

All gaily dressed soon you'll go

To the great Provincial show,

To be admired by many a beau

In the city of Toronto

Cows numerous as a swarm of bees,

Or as the leaves upon the trees,

It did require to make thee please,

And stand unrivalled, queen of cheese.

May you not receive a scar as

We have heard that Mr. Harris

Intends to send you off as far as

The great world's show at Paris.

Of the youth beware of these,

For some of them might rudely squeeze

And bite your cheek, then songs or glees

We could not sing, oh! queen of cheese.

We'rt thou suspended from balloon,

You'd cast a shade even at noon,

Folk would think it was the moon

About to fall and crush them soon.

I'm so grumpy this morning. I went to bed at half past midnight, which is not horribly late for a Friday. But one of the neighbours' cats woke me up at 5.50 am by miaowing outside my bedroom window. Having suggested to the little bastard that it relocated itself, I went back to bed.

I'd just dropped off when another set of neighbours started their car and left it idling in the drive way for ... oh ... ten minutes or so. This wouldn't be so bad but the drive runs along the side of my house. It's on concrete, with a brick wall on one side and a steel fence on the other. The sound is magnified. At the end of the ten minutes, they entire family packed into the car. Slam. Slam. Slam. Slam. And the boot. Slam. Off they went, with a jolly blast on the horn to Granma as they left. (Yeah, I know you can't shut a car door quietly but the bloody idling and tooting ... )

It gets worse. For some reason, just about everybody in the street left home at ten to fifteen minute intervals until 8 am. Then my alarm went off and I had to get up.

Why didn't I sleep in? Well, today may possibly be the day on which my side gate gets replaced. I hold no great hope that this will happen, but I have to be up and about on the off chance that the gate man will appear. At some time. In this dimension.

I'll keep you (gate) posted.

I'd just dropped off when another set of neighbours started their car and left it idling in the drive way for ... oh ... ten minutes or so. This wouldn't be so bad but the drive runs along the side of my house. It's on concrete, with a brick wall on one side and a steel fence on the other. The sound is magnified. At the end of the ten minutes, they entire family packed into the car. Slam. Slam. Slam. Slam. And the boot. Slam. Off they went, with a jolly blast on the horn to Granma as they left. (Yeah, I know you can't shut a car door quietly but the bloody idling and tooting ... )

It gets worse. For some reason, just about everybody in the street left home at ten to fifteen minute intervals until 8 am. Then my alarm went off and I had to get up.

Why didn't I sleep in? Well, today may possibly be the day on which my side gate gets replaced. I hold no great hope that this will happen, but I have to be up and about on the off chance that the gate man will appear. At some time. In this dimension.

I'll keep you (gate) posted.

Friday 22 September 2006

Great Northern!

Up over the hill loomed the grey dumps of the Deep Lead, until recent years one of the great alluvial tin-fields of Australia. A rumbling of thunder came from away back in the hills around Herberton where the reef miners were blasting the rock in their ceaseless search for tinstone. Enviously I wondered whether the shots were fired by the lucky Bimrose brothers, whether the murmurous thunder came from the Bradlaugh, the Lyee Moon, the Rainbow or Great Northern. Maybe the St Patrick or Black King—I'd hardly hear it from the Ironclad. Some of the big shows had struck rich patches of ore; how wonderful it must feel to be blasting out a rich crushing, with everyone in town wondering what percentage the stone would go! I could not imagine anything more wonderful. Just what could that heavy, dull, greyish-black stone mean to a man!

Ion Idriess

At the turn of the 19th century, Herberton was a town of tin miners and publicans. A hundred years later, the mines have closed and Herberton is more sedate. The story repeats along the western edge of the Atherton Tablelands: they came, they mined, they cut loose and then they left.

At the turn of the 19th century, Herberton was a town of tin miners and publicans. A hundred years later, the mines have closed and Herberton is more sedate. The story repeats along the western edge of the Atherton Tablelands: they came, they mined, they cut loose and then they left.Herberton is a short detour from the tourist route. It lies about 15 kilometres SSW of Atherton on a road that meanders pleasantly through state forest. The town straddles Wild River, where a quartet of prospectors discovered a tin lode in April 1880. They reported that the assays revealed 71% tin from the lode and even higher levels from alluvial (stream) deposits.

Within a couple of months, the Improvement Committee at Port Douglas commissioned Christie Palmerston to find a route to Wild River. His fee was £20. Palmerston, who had already carved out a track to the Hodgkinson goldfield, found a suitable road through the mountains. By August of that year, seventy miners had excavated over 100 tons of tin.

Within a couple of months, the Improvement Committee at Port Douglas commissioned Christie Palmerston to find a route to Wild River. His fee was £20. Palmerston, who had already carved out a track to the Hodgkinson goldfield, found a suitable road through the mountains. By August of that year, seventy miners had excavated over 100 tons of tin.Herberton had hit the big time.

The road was good in the dry season but became impassable in the wet. After a near disaster in 1882, when supplies did not reach the town for months, the miners lobbied for a railway. While blasting along the bank of the Wild River, the over-enthusiastic engineers blew the Presbyterian Church from its stumps. (It's not known whether that was really an accident ...) The track took almost thirty years to complete. The first train pulled into Herberton Station on 20th October 1910. The last one pulled out in 1989.

The road was good in the dry season but became impassable in the wet. After a near disaster in 1882, when supplies did not reach the town for months, the miners lobbied for a railway. While blasting along the bank of the Wild River, the over-enthusiastic engineers blew the Presbyterian Church from its stumps. (It's not known whether that was really an accident ...) The track took almost thirty years to complete. The first train pulled into Herberton Station on 20th October 1910. The last one pulled out in 1989.As you drive down the main street of Herberton today, it's difficult to imagine that less than 120 years ago it hosted the richest horserace outside Brisbane with a purse of £4000. Serious money. The town was the site of many firsts on the Tablelands. It boasted the first citrus orchard, first winery, first golf course, first race course, first dairy farm and the first brewery.

The Shire Council runs the Mining Centre on the site of the Great Northern Mine. The Centre is a local museum dedicated to the tin mining history of the area. It's a typical small museum—underfunded, underconserved but packed with fascinating material. A lucky dip of artefacts. I spent two hours there, which might have been the longest time anyone had stayed. But I was captivated by the history of the area and by the characters who had made the town their home over the past century or so. You'll hear all about them. Don't you worry about that!

The Shire Council runs the Mining Centre on the site of the Great Northern Mine. The Centre is a local museum dedicated to the tin mining history of the area. It's a typical small museum—underfunded, underconserved but packed with fascinating material. A lucky dip of artefacts. I spent two hours there, which might have been the longest time anyone had stayed. But I was captivated by the history of the area and by the characters who had made the town their home over the past century or so. You'll hear all about them. Don't you worry about that!

A little pea

Kennedia microphylla is an exquisite plant—a perfect miniature of its bigger, bolder cousins. Another Kennedia from south-western Australia, this species grows well in Melbourne. Although it prefers a free-draining soil, it seems to be doing well on my horrible clay. I planted it late last year and this is its first opportunity to flower. These are the first tiny blooms. I'm expecting heaps more.

Kennedia microphylla is an exquisite plant—a perfect miniature of its bigger, bolder cousins. Another Kennedia from south-western Australia, this species grows well in Melbourne. Although it prefers a free-draining soil, it seems to be doing well on my horrible clay. I planted it late last year and this is its first opportunity to flower. These are the first tiny blooms. I'm expecting heaps more. Among the other Kennedia species in my garden is this one: K. beckxiana. I won't write much about it now, except to say that I'm looking forward to it opening up. It has a huge scarlet flower. Very spectacular.

Among the other Kennedia species in my garden is this one: K. beckxiana. I won't write much about it now, except to say that I'm looking forward to it opening up. It has a huge scarlet flower. Very spectacular.

Death of a cedar

The short walk down to this last remaining giant tree only takes about ten minutes. Read the information signs along the way and learn about the logging history of this area. There are two separate viewing areas so that you can take in the sheer size of this colossal tree. Nobody knows why this lone tree was spared when all the others were logged. But it is a stark reminder of how logging has changed the nature of the rainforest.

(From the Wet Tropics Management Authority )

But even axe and saw couldn't compete with the thuggish force of Cyclone Larry. Winds from the tropical storm brought down the 500-year-old giant in March.

But even axe and saw couldn't compete with the thuggish force of Cyclone Larry. Winds from the tropical storm brought down the 500-year-old giant in March.The Gadgarra red cedar (Toona ciliata) was about 35 metres tall and 7 metres in diameter—an enormous tree that must have resisted many cyclones during its lifetime. But as the sign at the viewing platform says '... and along came Larry'.

Thursday 21 September 2006

Is Ian Rankin going to kill off John Rebus? Or will the inspector still lurk in the background when Siobhan takes over his role?

Things that make you go 'Ouch!'

(Or worse.)

We know that North Queensland's aquatic life can give you something to think about. But what of life on land? Is a wander through the rainforest fraught with danger?

Not really. Oh, sure, a cassowary can disembowel you. And an amethystine python might give you a friendly squeeze. But the fauna is otherwise pretty benign.

The plants are another matter.

Calamus, a genus of climbing palms, loves disturbed areas. You'll see thickets of it sprouting along the edges of forest paths or in clearings formed by fallen trees. Several species are common in the rainforests of Far North Queensland. All of them are covered in vicious spines. Just how vicious depends on the species.

Calamus, a genus of climbing palms, loves disturbed areas. You'll see thickets of it sprouting along the edges of forest paths or in clearings formed by fallen trees. Several species are common in the rainforests of Far North Queensland. All of them are covered in vicious spines. Just how vicious depends on the species.

Despite the weaponry, the larger Calamus palms are harvested for rattan. This industry is small in Australia but is a major one throughout South East Asia.

The spines on the stems of Calamus protect it from large herbivores. Those on the fronds and tendrils also make an unpleasant mouthful but they have another function: they act as grapnels when the plant is climbing. If you've ever been snagged on the wire-fine tendril of Calamus australis, you'll know how difficult it is to free yourself. They're called lawyer vines for a reason.

The spines on the stems of Calamus protect it from large herbivores. Those on the fronds and tendrils also make an unpleasant mouthful but they have another function: they act as grapnels when the plant is climbing. If you've ever been snagged on the wire-fine tendril of Calamus australis, you'll know how difficult it is to free yourself. They're called lawyer vines for a reason.

Still, Calamus is an amateur when it comes to inflicting pain. Stinging trees (Dendrocnide moroides) are much more effective. They look harmless enough, lining forest paths in the company of picturesque bangalow palms (Archontophoenix) and wild ginger (Alpinia) with their giant, heart-shape leaves and caterpillar-munched perforations. If an insect can chew on them, they can't be that bad. Right? Right?

Still, Calamus is an amateur when it comes to inflicting pain. Stinging trees (Dendrocnide moroides) are much more effective. They look harmless enough, lining forest paths in the company of picturesque bangalow palms (Archontophoenix) and wild ginger (Alpinia) with their giant, heart-shape leaves and caterpillar-munched perforations. If an insect can chew on them, they can't be that bad. Right? Right?

The sting probably won't kill you but you might well want to die if you brush up against the tree. Each leaf is covered in fine, hollow hairs made of silica, as sharp as broken glass and just as brittle. They snap off in the skin. But that isn't all. The hairs deliver tiny amounts of a neurotoxin. One hair, one microdose, no problem. Hundreds of hairs, hundreds of microdoses ... big problem.

The toxin is remarkably stable. It hangs around in the hairs for a long time. Contact with the affected area of skin will release it into the surrounding tissue, as will changes in temperature. And that includes hot water from showers or cool sea water. Apparently, the recommended solution for a sting is to apply those wax strips used in depilation.

The toxin is remarkably stable. It hangs around in the hairs for a long time. Contact with the affected area of skin will release it into the surrounding tissue, as will changes in temperature. And that includes hot water from showers or cool sea water. Apparently, the recommended solution for a sting is to apply those wax strips used in depilation.

But by far the best method is to avoid them. You know what they look like. Keep clear of the buggers. And never, ever use them as toilet paper.

We know that North Queensland's aquatic life can give you something to think about. But what of life on land? Is a wander through the rainforest fraught with danger?

Not really. Oh, sure, a cassowary can disembowel you. And an amethystine python might give you a friendly squeeze. But the fauna is otherwise pretty benign.

The plants are another matter.

Calamus, a genus of climbing palms, loves disturbed areas. You'll see thickets of it sprouting along the edges of forest paths or in clearings formed by fallen trees. Several species are common in the rainforests of Far North Queensland. All of them are covered in vicious spines. Just how vicious depends on the species.

Calamus, a genus of climbing palms, loves disturbed areas. You'll see thickets of it sprouting along the edges of forest paths or in clearings formed by fallen trees. Several species are common in the rainforests of Far North Queensland. All of them are covered in vicious spines. Just how vicious depends on the species.Despite the weaponry, the larger Calamus palms are harvested for rattan. This industry is small in Australia but is a major one throughout South East Asia.

The spines on the stems of Calamus protect it from large herbivores. Those on the fronds and tendrils also make an unpleasant mouthful but they have another function: they act as grapnels when the plant is climbing. If you've ever been snagged on the wire-fine tendril of Calamus australis, you'll know how difficult it is to free yourself. They're called lawyer vines for a reason.

The spines on the stems of Calamus protect it from large herbivores. Those on the fronds and tendrils also make an unpleasant mouthful but they have another function: they act as grapnels when the plant is climbing. If you've ever been snagged on the wire-fine tendril of Calamus australis, you'll know how difficult it is to free yourself. They're called lawyer vines for a reason. Still, Calamus is an amateur when it comes to inflicting pain. Stinging trees (Dendrocnide moroides) are much more effective. They look harmless enough, lining forest paths in the company of picturesque bangalow palms (Archontophoenix) and wild ginger (Alpinia) with their giant, heart-shape leaves and caterpillar-munched perforations. If an insect can chew on them, they can't be that bad. Right? Right?

Still, Calamus is an amateur when it comes to inflicting pain. Stinging trees (Dendrocnide moroides) are much more effective. They look harmless enough, lining forest paths in the company of picturesque bangalow palms (Archontophoenix) and wild ginger (Alpinia) with their giant, heart-shape leaves and caterpillar-munched perforations. If an insect can chew on them, they can't be that bad. Right? Right?The sting probably won't kill you but you might well want to die if you brush up against the tree. Each leaf is covered in fine, hollow hairs made of silica, as sharp as broken glass and just as brittle. They snap off in the skin. But that isn't all. The hairs deliver tiny amounts of a neurotoxin. One hair, one microdose, no problem. Hundreds of hairs, hundreds of microdoses ... big problem.

The toxin is remarkably stable. It hangs around in the hairs for a long time. Contact with the affected area of skin will release it into the surrounding tissue, as will changes in temperature. And that includes hot water from showers or cool sea water. Apparently, the recommended solution for a sting is to apply those wax strips used in depilation.

The toxin is remarkably stable. It hangs around in the hairs for a long time. Contact with the affected area of skin will release it into the surrounding tissue, as will changes in temperature. And that includes hot water from showers or cool sea water. Apparently, the recommended solution for a sting is to apply those wax strips used in depilation.But by far the best method is to avoid them. You know what they look like. Keep clear of the buggers. And never, ever use them as toilet paper.

You've seen the male Victoria's riflebird, resplendent in his blue satin and black taffeta. Here's the female. (Or possibly a juvenile. They look very similar.)

You've seen the male Victoria's riflebird, resplendent in his blue satin and black taffeta. Here's the female. (Or possibly a juvenile. They look very similar.)

Dear diary

Not such a bad day. I had to go to the dentist this morning but it picked up after that. Water cooler conversation meandered from Pre-Raphaelite artist William Holman Hunt to poets William Blake, John Donne, Andrew Marvell and Gerard Manley Hopkins (Walter de la Mare and Robert Graves got guernseys too), from the riots in Hungary to overthrowing the professoriat. Barely a mention of work. (Trust me, it's difficult to associate the professoriat with work.)

Then I came home. There appears to be some public event nearby. (It might be the Flemington Showgrounds.) Wherever it is, the PA system is turned up way too high. If I can locate the source, I might garotte the announcer with his own microphone cord. (And if it's a radio mike, I'm sure I can work out where to shove it.)

______________________________________

Let's figure this out ... At the Showgrounds. 21st September. That'd be the Royal Melbourne Show.

What a nitwit!

Then I came home. There appears to be some public event nearby. (It might be the Flemington Showgrounds.) Wherever it is, the PA system is turned up way too high. If I can locate the source, I might garotte the announcer with his own microphone cord. (And if it's a radio mike, I'm sure I can work out where to shove it.)

______________________________________

Let's figure this out ... At the Showgrounds. 21st September. That'd be the Royal Melbourne Show.

What a nitwit!

Wednesday 20 September 2006

This male Victoria's riflebird (Ptilorus victoriae) is one of a group that visited the lodge at Lake Eacham every morning on the hunt for handouts. Although this individual and its pals were used to humans, they were all very active and difficult to photograph.

This male Victoria's riflebird (Ptilorus victoriae) is one of a group that visited the lodge at Lake Eacham every morning on the hunt for handouts. Although this individual and its pals were used to humans, they were all very active and difficult to photograph.Victoria's riflebird is one of three Ptilorus birds of paradise in Australia. The males of all three have velvety black plumage with an iridescent blue cap, gorget and tail. The feathers on the belly are tipped with dark olive green. The name 'riflebird' is apparently derived from the similarity of the male's plumage to 19th century British military uniform. (I've said it before and I'll say it again: common names are just plain silly.)

A courting male attracts a female with a simple display in which he spreads his wings above his head in a dramatic pose. I saw them go through the same behaviour when two males disputed ownership of the diced apple on the bird table. The barneying birds also opened their bills wide to display bright yellow gapes. Very spectacular.

A courting male attracts a female with a simple display in which he spreads his wings above his head in a dramatic pose. I saw them go through the same behaviour when two males disputed ownership of the diced apple on the bird table. The barneying birds also opened their bills wide to display bright yellow gapes. Very spectacular.They dominated the bird table, seeing off Lewin's honeyeaters and any other small intruders. But a male met his match in a Macleay's honeyeater. Although these are more reserved that the cheeky Lewin's honeyeaters, one flew down to the table and stole a piece of fruit out of the riflebird's beak. There was plenty to go around. I think it was just making a point.

They are vocal birds, announcing their presence with unmusical rasping calls. Maybe they don't have to be melodious when they are so gorgeously clad? When they fly, the males make a sound like rustling taffeta. Because of that they are easy to detect—just listen for the noise of a ballroom dancer swishing past ... in the trees.

They are vocal birds, announcing their presence with unmusical rasping calls. Maybe they don't have to be melodious when they are so gorgeously clad? When they fly, the males make a sound like rustling taffeta. Because of that they are easy to detect—just listen for the noise of a ballroom dancer swishing past ... in the trees.

Tuesday 19 September 2006

Poooo!

Now why didn't I think of this one? Over the past two years, Dr Colin Lee and Professor Richard Wall of Bristol University have been studying the way in which insects colonise cattle dung. To minimise the variation between poos, they constructed artificial pats, each weighing exactly 1.5 kilograms.